Overview

The U.S. freight rail system serves as a critical component of the national economy, transporting bulk commodities and manufactured goods while connecting production centers, consumer markets, and international trade gateways. Rail freight volumes function as key economic indicators, reflecting structural economic adjustments, industrial distribution changes, and global trade dynamics.

Historical Context

American rail freight traces its origins to the early 19th century, emerging as a vital transportation network during the Industrial Revolution that linked the nation's coasts and facilitated commerce. The late 19th through early 20th century marked rail's golden age, with expansive networks driving economic expansion. While highway and air transport later eroded rail's market share, recent environmental concerns and energy efficiency priorities have renewed interest in rail as a sustainable transportation solution.

Current Landscape

Commodity Composition

U.S. rail freight handles diverse cargo categories:

- Coal: Historically dominant but declining due to clean energy transitions

- Grain: Essential for domestic consumption and agricultural exports

- Chemicals: Critical industrial feedstock transportation

- Metals: Ore and finished product movement for manufacturing

- Construction Materials: Stone, cement, and aggregates for infrastructure

- Intermodal: Container/trailer combinations leveraging multiple transport modes

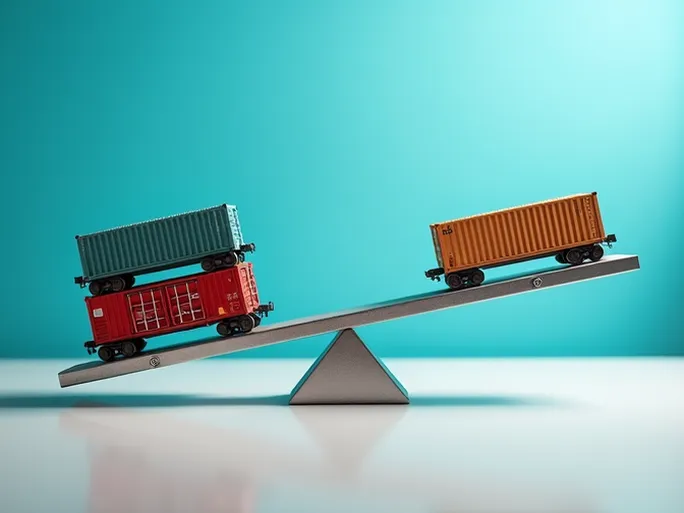

Volume Trends

Recent years show complex patterns in carload and intermodal metrics. Carload volumes fluctuate with economic cycles and energy policies, while intermodal shipments demonstrate consistent growth as an efficiency solution.

Major Operators

The sector features dominant Class I railroads:

- Western Networks: Union Pacific and BNSF Railway

- Eastern Networks: Norfolk Southern and CSX Transportation

- Transnational Operators: Canadian National and Canadian Pacific

Operational Challenges

Competitive Pressures

Rail competes with trucking's flexibility, maritime's cost efficiency, and pipelines' specialized transport capabilities, necessitating continuous operational improvements.

Infrastructure Concerns

Aging track systems and bridges require substantial modernization investments to maintain safety and service reliability.

Regulatory Environment

Safety, environmental, and labor regulations significantly impact operational frameworks and cost structures.

Technological Adoption

Automation, smart systems, and emission-reduction technologies present both implementation challenges and efficiency opportunities.

Labor Dynamics

Workforce management remains crucial, with recent labor disputes highlighting the need for sustainable employee relations.

Climate Factors

Extreme weather vulnerability, coastal infrastructure risks, and energy transition impacts require adaptive strategies.

Strategic Outlook

Growth Catalysts

Economic expansion, demographic trends, trade flows, environmental priorities, and energy advantages position rail for potential resurgence.

Industry Evolution

Key development vectors include:

- Intermodal integration as the operational standard

- Digital transformation through intelligent systems

- Sustainability-focused operational models

- Customized logistics solutions

- Cross-modal transportation partnerships

Policy Considerations

Strategic recommendations emphasize infrastructure funding, regulatory modernization, technology incentives, international coordination, and climate resilience planning.

Conclusion

The U.S. freight rail system stands at an inflection point, balancing traditional strengths against modernization requirements. Its ability to adapt to economic, technological, and environmental realities will determine its future role in national logistics networks. Both private sector innovation and public policy support appear essential for maintaining rail's competitive position in 21st-century transportation systems.